Queer Iconography, Daddy Issues and Chain Smoking, Lily Sinko's ‘Magdalena: Woman of Joy’, A New Comedy

- Grace Mahoney

- Jun 11, 2025

- 4 min read

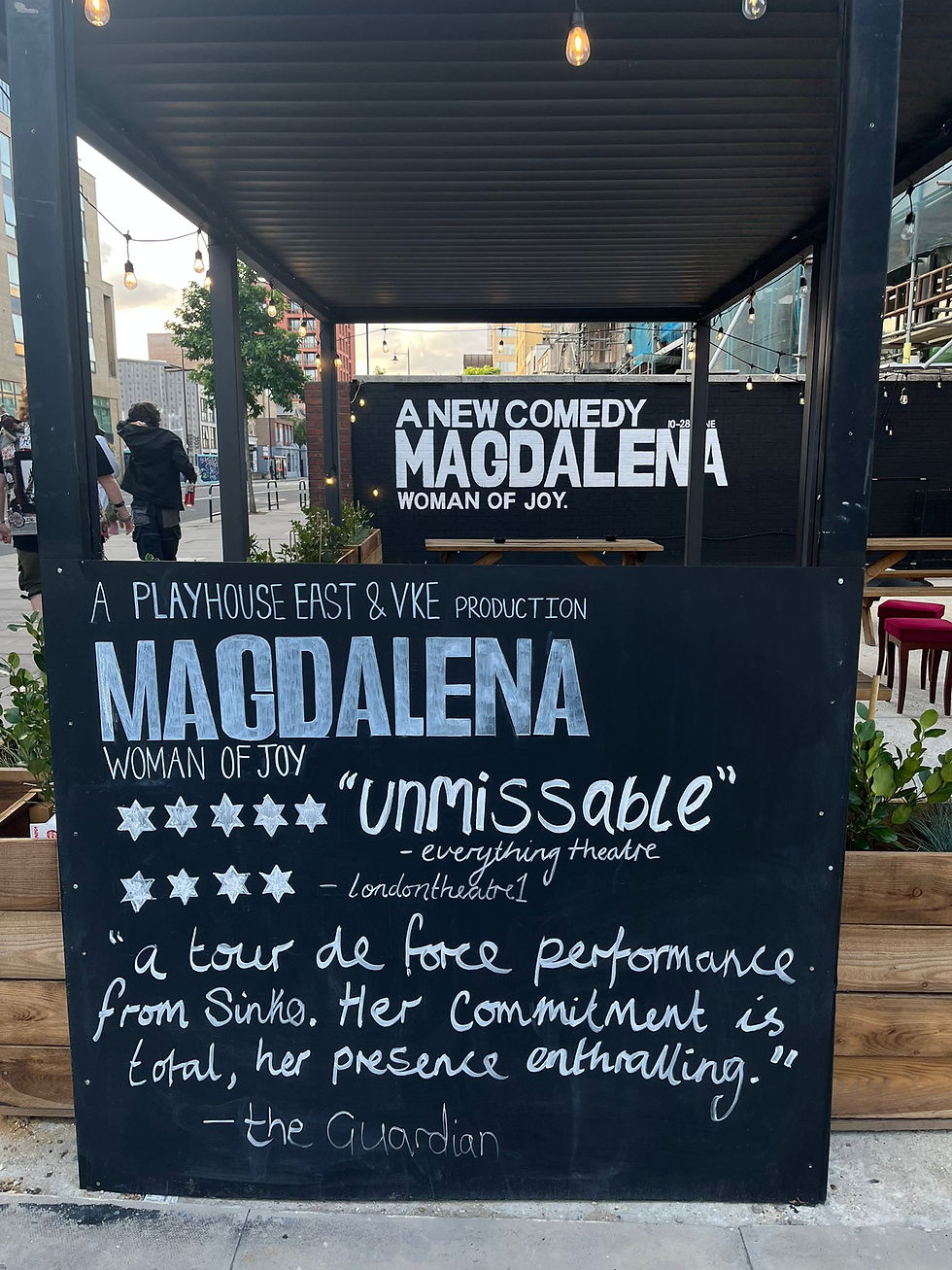

Writer and leading woman Lily Sinko brought a new, unique comedy entitled, ‘Magdalena: Woman of Joy’ to Playhouse East from the 10th to the 28th of June. The Haggerston-based 100 seat theatre space was decorated with the lighting and ambience of a speakeasy, where the adventures that created the flamboyance of Magdalena’s character seemed more like a conversation over drinks and cigarettes, rather than a scripted act. Enriched by her spirit and electric performative presence, Sinko’s portrayal of French prostitute Magdalena was enlivened through drag, explicit taboos and the multiplicity of characters enacted in this one woman show. Following her life from one outlandish story to another, the play's hilarity resided within its vulgarity, its descent into frantic madness and engulfment by queer iconography, and distorted daddy issues. The show began with Magdalena appearing out of the darkness, cigarette in hand, scanning the audience with a fixed stare and a scowl, before fixing on a man in the front row stating, ‘You want to fuck me? That’s okay I want to fuck me too’. Inevitably, from the first moments of the play, Magdalena presents herself decisively as a force to be reckoned with, not one to be sorry for. Beginning in a small rural town in France, we accompany Magdalena through her harrowing childhood, experiencing the emotions of abandonment as her father leaves her to be taken to ‘the school for bad, bad girls (cash only)’. We soon discover that behind the animation of Magdalena’s storytelling lies a life story littered with trauma and horror, from childhood abandonment, entraped sex work, aggressive abortions and eventually seeking solace in a church, Magdalena’s life is haunted by her childhood. We gradually move through each enacted space with a light heart and a laugh at the hands of Sinko’s projection of Magdalena’s life consequently overshadowing its true horror.

Sinko worked to integrate us as playgoers not just into the play but into the story itself. She took the place of characters and added a dimension that’s unpredictable and consequently hilarious. She brought audience members into the space of the stage on two occasions: once to fumble over the reenactment of a conversation between Magdalena and her first love and then janitor at ‘the school for bad, bad girls (cash only)’. We see in motion Magdalena’s rage, that led her to bite the janitor's finger off, embodied by the specially selected audience member, in a dramatised fight where Magdalena recalled falling and dragging the Janitor from the school’s roof and ‘standing on his back like a surfboard’. Both the absurdity of the story and the bewilderment of the audience member make the interaction uproariously funny. This was not an act in isolation as Magdalena scans the audience asking who has ‘ever been in love’ and the audience member who answers they were unable ‘to keep that love’ is brought forward to allow Magdalena to ‘teach’ the act of seduction, through exaggerated movements and kissing towards the audience. These ‘willing’ participants only added to the comedic aspect of the play, where Sinko’s puppetering of the audience creates a space for comedic aspects of the story to be enriched by us as outsiders. Sinko’s unfiltered mannerism and gesticulation move the story out of any state of stagnation to be as chaotic as the adventures themselves. From the mysterious disappearances of her pregnant school friends, to being burnt alongside her Stepmother Caroline, Sinko’s exuberance and definition of character created clarity in the chaos. Where Magdalena’s life lacked serenity, Sinko’s writing craft and cohesiveness allowed for the audience to follow through the turmoil of Magdalena’s life. From feeling empathy for her as a child to sharing her empowerment as she harnessed her sexuality, Magdalena is a character like none other. There is a lot to be said about Magdalena, but there is even more to be said about Sinko in her performance. Without her capacity to turn a small theatrical space into the harrowing story of an outcast yet inspiringly empowered French prostitute, the story perhaps lacks a direct sense of purpose. However, Sinko’s movements, gesticulation and general exuberance of performative spirit allows us as an audience to miss this fact, we shift our focus perhaps from seeking a purpose in the story to trying to keep up with Sinko’s cartoonish recollection of events.

The play drew to a close with the ostracisation of Magdalena, closing in on ideas of witchcraft and prostitution, by Magdalena being burnt at the stake for sleeping not only with the whole parish but the whole village. Where her fathers red glitter boots leave us stunned as he transforms from a con artist to a high priest, we see the power of gender in the story once again rear its gruesome head. Questioning Saintliness, iconoclasm and overt sexuality in holy spaces, Magdalena becomes the female form of sin…if the devil wore fishnet stockings and red lipstick. Magdalena’s death at the stake moves the narrative perspective from the place of a ghost, where Magdalena recalls her moment of death, her forced repentance at the stake and the cyclical abandonment from her father and her religion. We, as the audience, accompanied Magdalena on a rollercoaster of emotions, feeling and experiencing all that she did. Our connection to Magdalena is made possible by the gift of Sinko, and the unfiltered emotion and the seamlessness in which she performs them. The horrors of Magdlena’s life become overshadowed by the animation in which they are told, taking a story about child prostitution and abandonment and channeling them into comedy through Sinko's bold portrayal of a woman discarded. Magdalena’s refreshing rawness and transparency in a character so downtrodden in luck is what gave the play so much spirit and space for comedy. An incredible performance and a rising performer worth remembering.

Written by Grace Mahoney

Edited by Daria Slikker, London Editor

Comments